Apr 2025

Territorial Shifts in Modern European History: From Treaties to Tensions

From Invasion and Annexation to Self-Determination

Throughout modern history, territories have frequently been acquired through treaties imposed by victorious powers. Defeated nations often harboured ambitions to reclaim lost lands, setting the stage for later conflicts. Russia’s influence over Eastern Europe fluctuated dramatically from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, as borders were repeatedly redrawn by both diplomacy and force. Over time, however, this dynamic shifted toward recognising the right of peoples to self-determination, with democratic elections increasingly replacing the coercive transfer of territory.

Case Study: Ukraine’s Historical Trajectory

Early Origins and Commonwealth Era (1187–1783)

The earliest reference to a polity identified as "Ukraine" appears in 1187 within chronicles of the Kievan Rus’. Over subsequent centuries, Ukrainian territories fell under the sway of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the mid-seventeenth century, the Cossack Hetmanate emerged as a semi-autonomous Cossack state, but was ultimately subsumed by neighbouring empires.

Imperial Control and Cultural Suppression (1783–1917)

From 1783, Ukraine became formally part of the Russian Empire. In 1863 the Valuev Circular was issued, forbidding publication in the Ukrainian language; this edict was reinforced in 1876, further banning Ukrainian-language instruction and press.

Brief Independence and Soviet Conquest (1917–1919)

In the aftermath of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917, the Ukrainian People’s Republic declared independence in January 1918. Later that year, the West Ukrainian People’s Republic was proclaimed in Lviv. These nascent states were short-lived; by 1919, Soviet forces invaded to install a Moscow-aligned government. The conflict continued until the Treaty of Riga was signed in March 1921 between Poland and Soviet Russia, with Lenin opting for peace. Backed by the Ukrainian People’s Republic, Poland had resisted Red Army attempts to advance through its territory toward Germany and spread the socialist revolution. The treaty recognised Latvia’s independence, incorporated Ukraine and Belarus into the USSR, and brought an end to hostilities that had included the last great cavalry battle—costing around 120,000 lives and leaving many more wounded.

Stalinist Repression and the Holodomor (1920s–1930s)

The interwar period under Soviet rule was marked by mass dispossession and forced labour in the Gulag system. Stalin’s Great Terror targeted the Ukrainian intelligentsia, and the Holodomor famine of 1932–1933 led to the deaths of millions through state-engineered starvation.

World War II and Post-War Recovery (1939–1954)

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, signed on 23 August 1939, contained secret protocols that remained undisclosed until 1989. These clauses outlined a deliberate partitioning of Eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, along with provisions for economic cooperation—including deliveries of raw materials. The agreement allocated Lithuania to Germany, while the USSR claimed the right to occupy Estonia and Latvia and asserted control over Finland and Bessarabia. Before the Nazi invasion of the USSR in 1941, Soviet repressions affected some 500,000 Poles, including the deportation of 340,000, the deaths of 100,000 in camps, and the execution of at least 30,000, notably Polish officers in the Katyn massacre. The Soviets and Nazis explicitly acknowledged their "brotherhood in arms" through joint military parades, such as the one in Brest-Litovsk, and by signing a further Treaty of Friendship on 28 September 1939. Soviet and Nazi secret police—NKVD and Gestapo—also cooperated to eliminate the Polish resistance. The secret protocol of August 1939 granted the USSR freedom to attack Finland without fear of German retaliation, given that the two regimes remained military partners at that time. The Soviet invasion of Finland began in November 1939, and the territories seized were never returned. When Hitler’s troops captured Paris, Stalin congratulated him via telegram, stressing that France and Britain were responsible for starting the war.

Observing the Red Army’s costly and demoralising Winter War against Finland—where Soviet forces suffered heavy losses and failed to achieve their objectives—Hitler concluded that Stalin’s military was both weak and overextended. Seizing this perceived advantage, he broke the Brest-Litovsk pact and launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, aiming to crush the USSR before it could recover. German forces quickly advanced deep into Soviet territory, reaching the outskirts of Moscow by December. Soviet counter-offensives, bolstered by Allied matériel from the United States, United Kingdom and France, gradually pushed the Wehrmacht back and recaptured occupied regions by 1944.

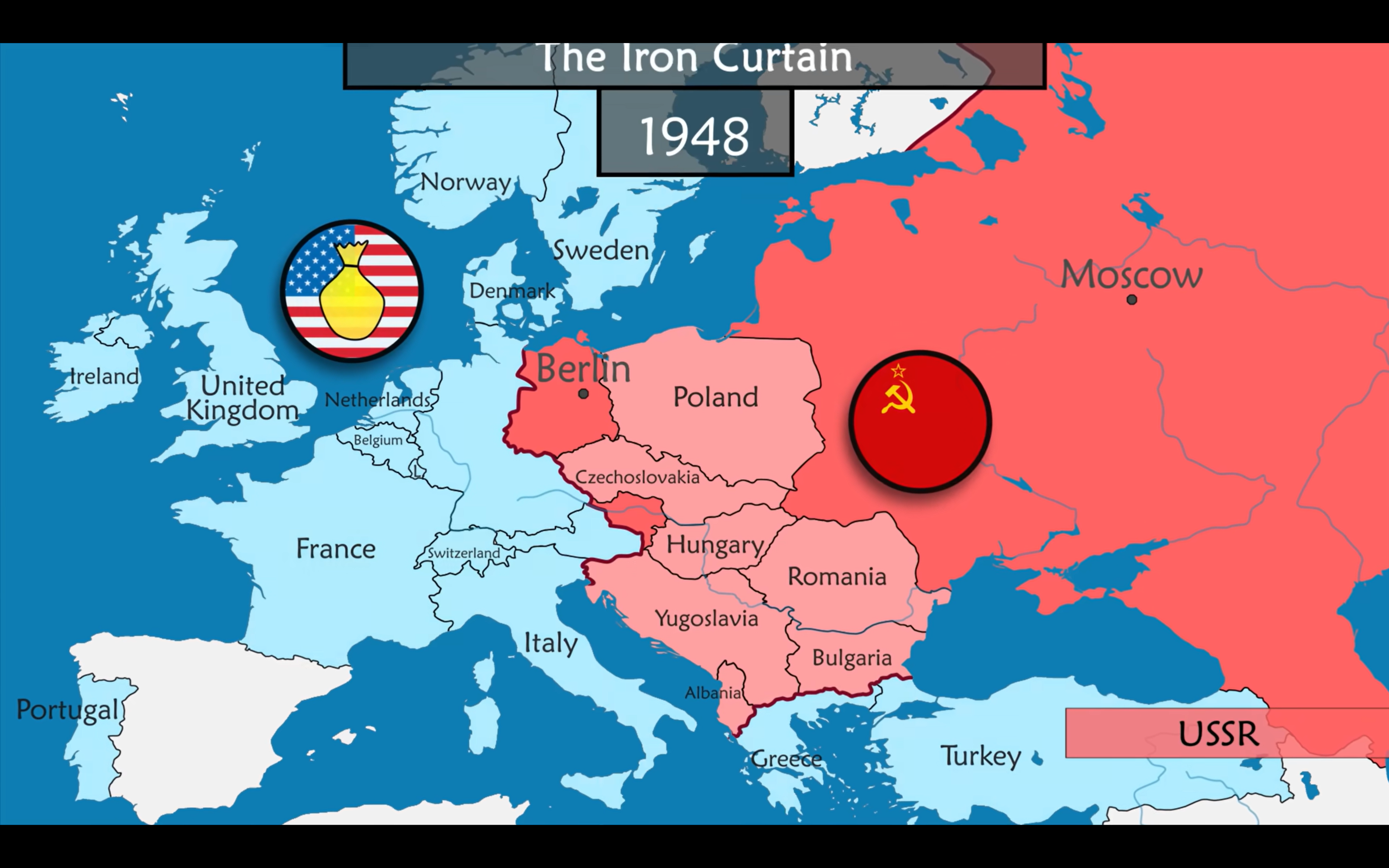

At the February 1945 Yalta Conference, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin reached an accord that effectively granted the Soviet Union domination over much of Eastern Europe. Despite Stalin’s earlier pact with Hitler to carve up the region in 1939, the Western Allies—concerned above all with securing Soviet commitment to continue the war against Japan and to participate in the newly formed United Nations—reluctantly consented to Soviet “spheres of influence” in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and the Baltic states. Roosevelt, impressed by Stalin’s firm leadership and eager to maintain Allied unity, adopted a conciliatory stance, while Churchill, though more sceptical, lacked the means to oppose the decision without risking a fracture in the grand alliance. The result was a de facto sanctioning of Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe, laying the groundwork for the Cold War division of the continent.

By 1954, the centrally planned USSR economy suffered severe shortages; most citizens could not afford consumer goods such as cars or televisions, fuelling nascent nationalist sentiment in Ukraine.

Decline of the Soviet Regime (1955–1991)

Between the mid-1950s and the late 1980s, the Soviet Union faced mounting economic stagnation, widespread shortages, and a lack of political innovation. By the 1980s, it became evident that the USSR could not compete economically with the West. Repression of dissidents and limited personal freedoms only worsened the perception of the regime among its republics. The Chernobyl disaster in 1986, poorly managed by Soviet authorities, further delegitimised the central government. These factors accelerated the loss of faith in the Communist Party across the bloc.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness) in the mid-1980s aimed to reform the Soviet economy and society. However, these reforms inadvertently unleashed nationalist sentiments across the republics, including Ukraine. The Ukrainian Popular Front emerged as a significant political force, advocating for independence and democratic reforms.

Independence and Post-Soviet Challenges (1991–2014)

On 24 August 1991, the Ukrainian parliament declared independence, and a referendum later that year saw over 90% support, including overwhelming majorities in regions such as Kyiv, Lviv, and even Crimea. However, corruption and economic stagnation persisted, particularly affecting the industrial eastern oblasts like Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk. Viktor Yanukovych’s election in 2010 on a pro-Russian platform was followed by the Euromaidan protests of late 2013 and early 2014, centred in Kyiv’s Independence Square and spreading across major cities, which ousted him in favour of a pro-European government.

Annexation of Crimea and Ongoing Conflict (2014–present)

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014 was precipitated by the Euromaidan protests and the ousting of President Yanukovych in February 2014. Within days, unmarked Russian forces occupied key facilities across Crimea under the pretext of protecting ethnic Russians. President Putin publicly framed the move as a response to NATO’s eastward expansion threatening Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol. On 16 March 2014, a hastily organised referendum under military occupation claimed overwhelming support for joining Russia, though it was declared illegal by the OSCE. The UN General Assembly then adopted Resolution 68/262, affirming Ukraine’s territorial integrity and invalidating the referendum. Most Western governments condemned the annexation and refused to recognise Russia’s claims, imposing sanctions in turn. Concurrently, Russia began backing separatist movements in the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts, sparking a protracted conflict in eastern Ukraine. Despite the Minsk ceasefire agreements, hostilities persisted until the 24 February 2022 full-scale invasion. Russian forces initially advanced toward Kyiv via Belarus and secured gains in the Donbas, Mariupol, and Kherson regions. Ukrainian counter-offensives later recaptured parts of Kharkiv and the western bank of the Dnipro River in Kherson Oblast.

Analogous Interventions

Historical precedents underscore how great powers, notably Russia and its Soviet predecessor, have routinely intervened militarily to enforce ideological or strategic interests. The brutal suppression of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring in 1968 under Leonid Brezhnev, exemplified Moscow’s determination to quash liberalising movements within its sphere of influence. In 1979, following a series of anti-Soviet revolts in Kabul and other Afghan cities, the Soviet Union deployed troops to Afghanistan, initiating a decade-long occupation marked by repression and high civilian casualties. These successive acts of coercion contributed to growing disillusionment within the Eastern Bloc, eventually leading to the fragmentation of the Warsaw Pact and the resurgence of national independence movements, particularly in the Baltic States and among other former Soviet republics. Ukraine’s case, however, appears exceptional due to the scale, duration, and symbolism of the war.

NATO Expansion & Response

The eastward expansion of NATO, beginning in the late 1990s, is often cited by Russian policymakers as a threat to their national security. Former Soviet republics and Warsaw Pact states joined NATO voluntarily, seeking security guarantees and integration with Western institutions. Moscow perceived this realignment as a strategic encirclement. Yet, such realignments stem from sovereign decisions by nations disillusioned with the legacy of Soviet dominion.

Vision: Russia’s True Interest

It is in Russia’s long-term interest to abandon imperial nostalgia and focus instead on its internal modernisation. Continuing to pursue influence through coercion and force only isolates Russia diplomatically and economically. A future-oriented Russia should invest in education, technology, infrastructure and civil liberties—building a nation that others aspire to emulate rather than fear.

At this stage, Ukraine has made its choice. Its sovereignty is internationally recognised, and its people have shown, again and again, their determination to live in a democracy. No legitimate solution can be reached by trying to force Ukraine into subjugation.

In an era where wars of conquest no longer lead to prosperity, true power lies in a nation’s ability to inspire, not dominate. History, if it teaches us anything, rewards those who trade oppression for opportunity and militarism for meritocracy.